We’re all still recovering from Tuesday night. Surprise wins for both Kendra Brooks and David Oh turned the Philadelphia political world on its head. I won’t waste your time narrating what others will write better. Let’s look at some numbers, with 99% of Divisions reporting.

Helen Gym paced the way with 15.3% of the vote. None of the Democrats lost. But most importantly, we’ll consider the two surprises: Kendra Brooks and David Oh.

View code

library(sf)

library(tidyverse)

load_data <- function(file){

df <- read_download(file)

df %<>%

filter_divs_and_offices() %>%

format_columns()

return(df)

}

read_download <- function(file){

colnames <- read_csv(file, n_max = 1, col_names=F) %>% unlist()

candidates <- read_csv(file, n_max = 1, skip=1, col_names=F) %>% unlist()

df <- read_csv(file, skip=2, col_names=F) %>%

rename(warddiv=X3) %>%

select(-X1, -X2) %>%

pivot_longer(values_to="votes", names_to="key", -warddiv) %>%

filter(!is.na(votes)) %>% ##only removes X119

mutate(key = asnum(gsub("^X", "", key))) %>%

mutate(office = colnames[key], candidate=candidates[key]) %>%

mutate(

party = gsub("(.*) \\((.*)\\)$", "\\2", candidate),

candidate = gsub("(.*) \\(.*\\)$", "\\1", candidate),

office = ifelse(office == "COUNCIL AT-LARGE", "COUNCIL AT LARGE", office),

office = ifelse(candidate %in% c('JUDY MOORE', "BRIAN O'NEILL"), "DISTRICT COUNCIL-10TH DISTRICT", office)

) %>%

select(warddiv, office, candidate, party, votes) %>%

filter(warddiv != "COUNTY TOTALS")

return(df)

}

filter_divs_and_offices <- function(df){

returns <- df %>%

group_by(warddiv) %>%

summarise(sum_votes = sum(votes)) %>%

group_by() %>%

filter(sum_votes > 0)

df <- df %>% inner_join(returns %>% dplyr::select(warddiv))

if(nrow(df) == 0) stop("No data yet!")

df <- df %>%

filter(office %in% CONFIG$offices) %>%

filter(!candidate %in% c("Write-In", "Write In"))

return(df)

}

format_columns <- function(df) {

df <- df %>%

mutate(candidate = format_candidate_name(candidate)) %>%

group_by(warddiv, office) %>%

mutate(pvote = votes / sum(votes)) %>%

group_by()

return(df)

}

format_candidate_name <- function(x){

x <- gsub("^[0-9]+\\-", "", x)

x <- gsub("(.*)\\,.*", "\\1", x)

x <- format_name(x)

return(x)

}

CONFIG <- list(offices = c("MAYOR", "COUNCIL AT LARGE"))

ELECTION <- "20191105"

USE_LOG <- TRUE

df <- load_data(

"../election_night_needle/raw_data/results_20191107_194343.csv"

)

divs <- st_read("../../data/gis/201911/Political_Divisions.shp") %>%

mutate(warddiv=pretty_div(DIVISION_N))wards <- st_read("../../data/gis/2019/Political_Wards.shp") %>%

mutate(ward=sprintf("%02d", asnum(WARD_NUM)))div_cats <- readRDS(

most_recent_file("../../data/processed_data/div_cats_")

)

at_large_table <- df %>%

filter(office == "COUNCIL AT LARGE") %>%

group_by(candidate) %>%

summarise(votes=sum(votes)) %>%

mutate(

pvote=100*votes/sum(votes)

) %>%

arrange(desc(pvote))

knitr::kable(

at_large_table,

digits=1,

col.names=c("Candidate", "Votes", "% Vote"),

format.args=list(big.mark=',')

)| Candidate | Votes | % Vote |

|---|---|---|

| Helen Gym | 187,161 | 15.3 |

| Isaiah Thomas | 178,571 | 14.6 |

| Katherine Gilmore Richardson | 172,435 | 14.1 |

| Derek S Green | 172,264 | 14.1 |

| Allan Domb | 169,395 | 13.9 |

| Kendra Brooks | 55,599 | 4.6 |

| David Oh | 49,700 | 4.1 |

| Al Taubenberger | 44,084 | 3.6 |

| Nicolas O’Rourke | 43,012 | 3.5 |

| Dan Tinney | 42,962 | 3.5 |

| Bill Heeney | 40,187 | 3.3 |

| Matt Wolfe | 38,341 | 3.1 |

| Sherrie Cohen | 8,354 | 0.7 |

| Joe Cox | 8,229 | 0.7 |

| Maj Toure | 5,676 | 0.5 |

| Steve Cherniavsky | 3,225 | 0.3 |

| Clarc King | 2,731 | 0.2 |

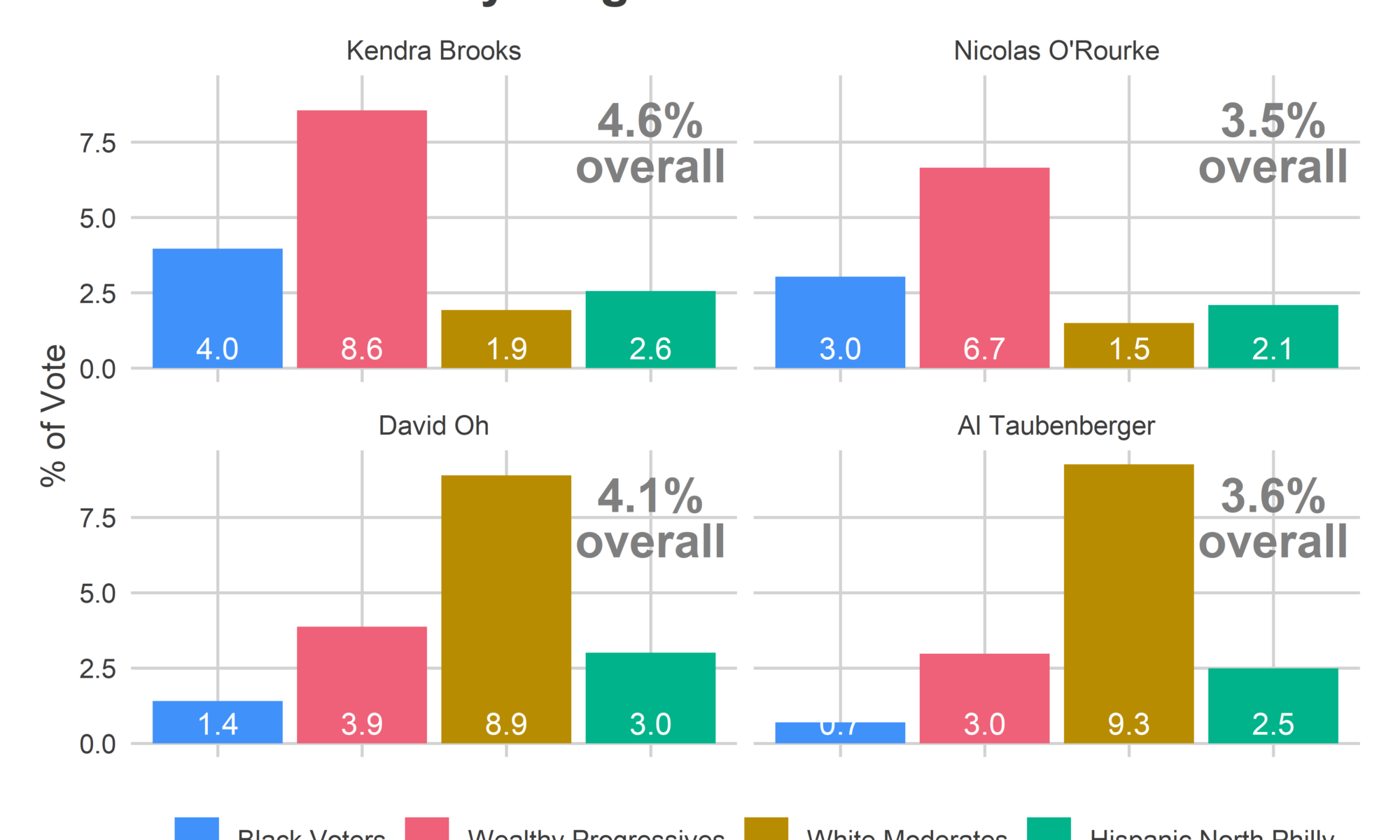

First, the turnout. With 99% of divisions reporting, we’re at an unprecedented count of 295,955. (You all helped me predict that. We’ll talk about that in a future post. ::sunglassesemoji::)

The post-2016 surge in turnout continued, with South Philly, Fairmount, and University City pacing the city.

View code

TURNOUT_OFFICE <- "COUNCIL AT LARGE"

turnout_19 <- df %>%

filter(office==TURNOUT_OFFICE) %>%

group_by(warddiv) %>%

summarise(turnout=sum(votes))

ward_turnout_19 <- turnout_19 %>%

mutate(ward=substr(warddiv,1,2)) %>%

group_by(ward) %>%

summarise(turnout=sum(turnout))

ggplot(

divs %>%

left_join(turnout_19) %>%

mutate(turnout_per_sf=turnout/as.numeric(st_area(geometry)))

) +

geom_sf(aes(fill=1609^2 * pmin(turnout_per_sf, 0.025)), color=NA) +

scale_fill_viridis_c("Votes per mile", labels=scales::comma) +

theme_map_sixtysix() +

ggtitle("Votes Cast per Mile", "Council At Large")

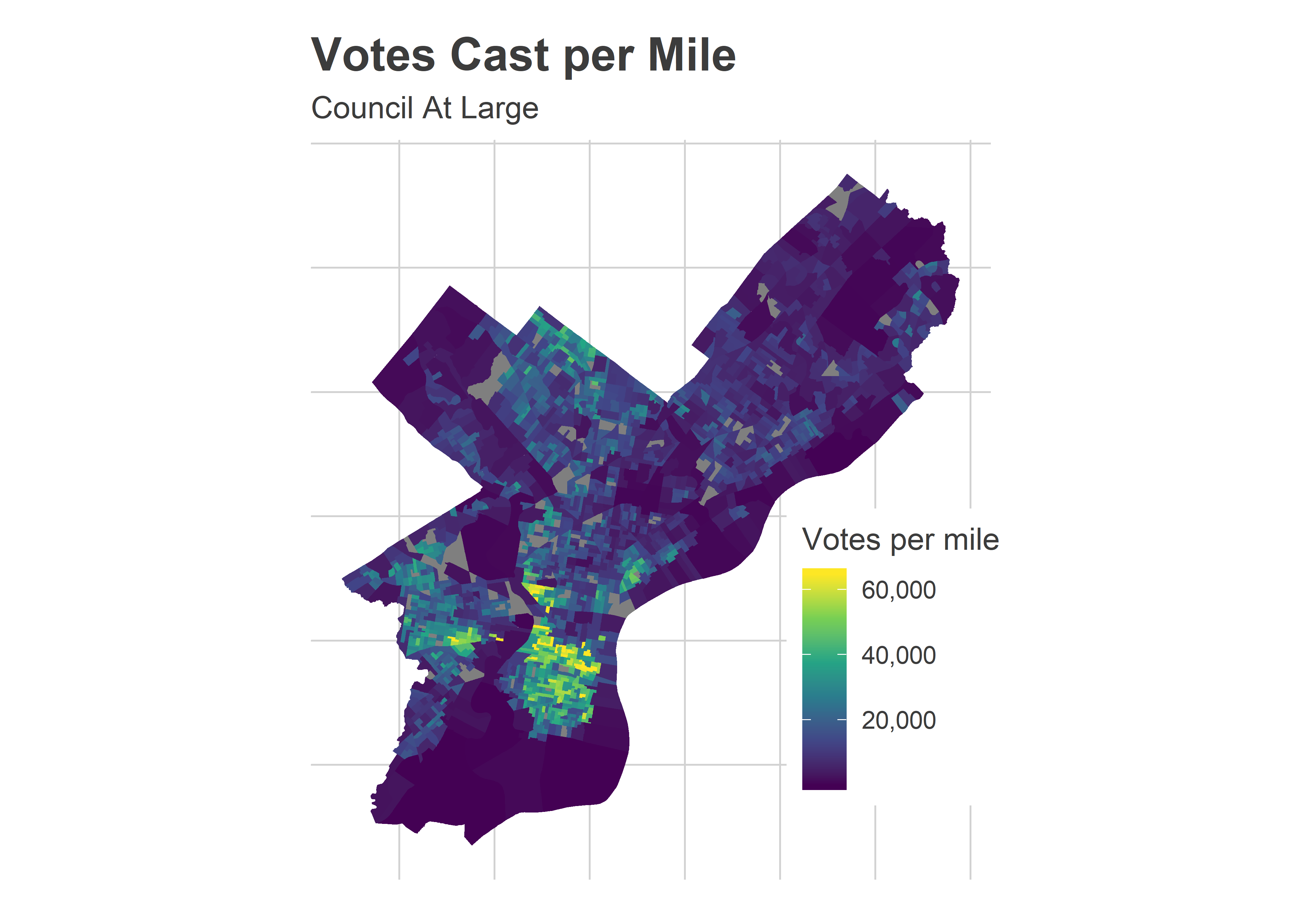

Every single ward voted more than in 2015. And this race had an incumbent mayor.

View code

valid_divs <- unique(df$warddiv)

df_past <- readRDS("../../data/processed_data/df_major_2019-11-07.Rds") %>%

mutate(warddiv=pretty_div(warddiv)) %>%

filter(warddiv %in% valid_divs)

comp_year <- 2015

turnout_comp <- df_past %>%

filter(

year==comp_year,

election=="general",

office==TURNOUT_OFFICE

) %>%

group_by(warddiv) %>%

summarise(turnout=sum(votes))

ward_turnout_comp <- turnout_comp %>%

mutate(ward=substr(warddiv,1,2)) %>%

group_by(ward) %>%

summarise(turnout=sum(turnout))

ggplot(

wards %>%

left_join(ward_turnout_comp) %>%

left_join(ward_turnout_19, by="ward", suffix=c(".comp", ".19")) %>%

mutate(turnout_ratio = turnout.19 / turnout.comp)

) +

geom_sf(aes(fill=turnout_ratio), color=NA) +

scale_fill_viridis_c("Votes cast,\n 2019 / 2015") +

theme_map_sixtysix() +

ggtitle("Change in votes cast, 2015 - 2019", "Council At Large")

But the increase wasn’t evenly spread, and that helped Brooks. The biggest changes came from the ring around Center City, including Fishtown’s wards 18 and 31 (+91% and 84% more votes, respectively), and South Philly’s 1 and 48 (+66% and 65%). They’re not terrible bright on the map, though, because University City’s 27 (+109%) breaks the color scale.

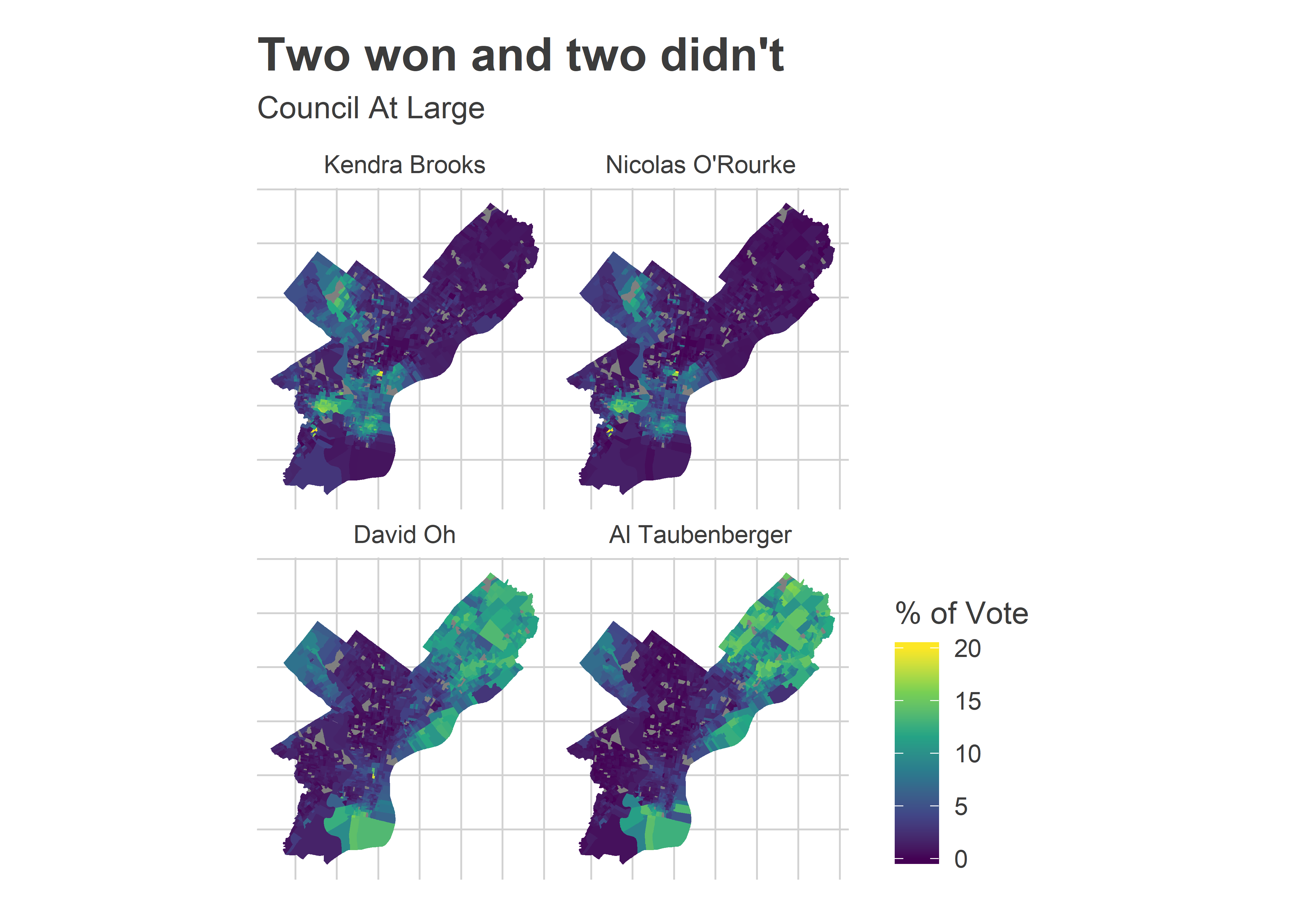

Two candidates who won, and two who didn’t

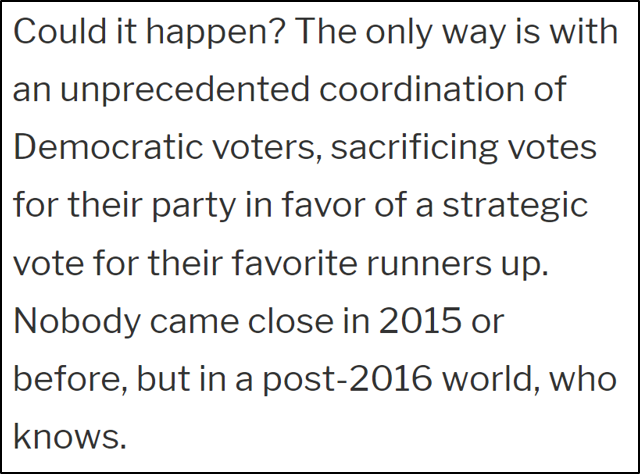

Brooks and Oh won by different paths. Brooks dominated the Wealthy Progressive divisions and did well enough in Black divisions to cruise to victory. Oh did predictable well in the Northeast, and inched ahead of his competition by eking out votes in Democratic strongholds.

To illustrate just how narrow each of their paths to victory were, let’s consider the electoral doppleganger of each: Nicolas O’Rourke and Al Taubenberger.

View code

use_candidates <- c(

"Kendra Brooks", "Nicolas O'Rourke", "David Oh", "Al Taubenberger"

)

at_large_df <- df %>%

filter(

office=="COUNCIL AT LARGE",

candidate %in% use_candidates

) %>% mutate(candidate=factor(candidate, levels=use_candidates))

total_votes <- df %>%

filter(office == "COUNCIL AT LARGE") %>%

group_by(warddiv) %>%

summarise(total_votes=sum(votes))

ggplot(

divs %>%

# add NA divs

left_join(

expand.grid(warddiv=divs$warddiv, candidate=use_candidates)

) %>%

left_join(at_large_df)

) +

geom_sf(aes(fill=100*pmin(pvote, 0.2)), color=NA) +

scale_fill_viridis_c("% of Vote") +

theme_map_sixtysix() %+replace%

theme(legend.position = "right") +

facet_wrap(~candidate, ncol=2) +

ggtitle("Two won and two didn't", "Council At Large")

It’s hard to tell the difference between the winners and losers from these maps. Kendra and Nicolas both dominated the Wealthy Progressive divisions of University City, South Philly, and Chestnut Hill; David and Al the Republican leaning Northeast, upper River Wards, and deep South Philly. You wouldn’t necessarily guess that Kendra would win but Nicolas wouldn’t, or that David would win without Al doing so, too.

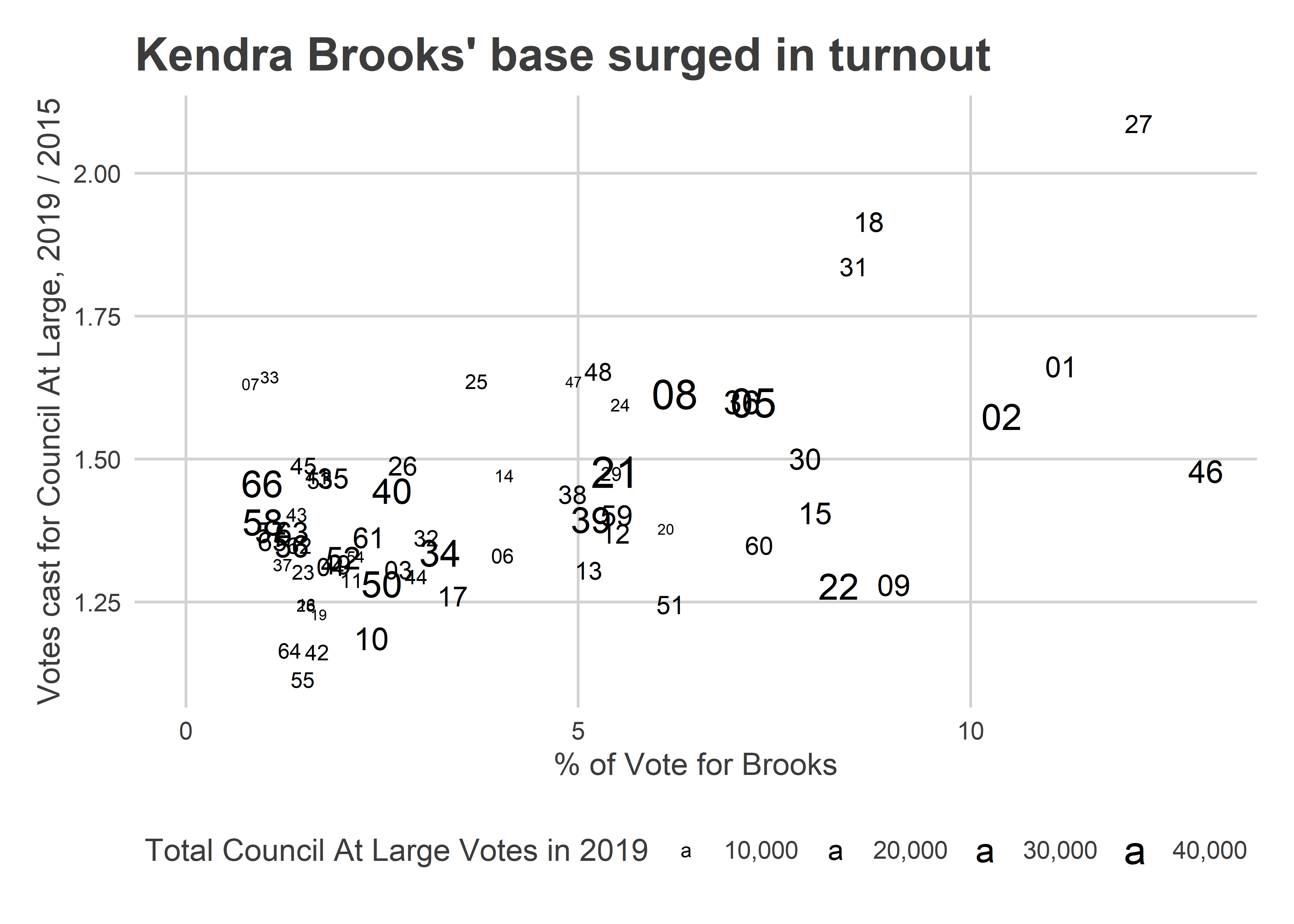

But first, why was the race such a romp for Brooks? Notice the overlap between her map and the turnout map above. She enormously excited her base: the divisions where she won were also the ones that turned out at unprecedented rates.

View code

ggplot(

df %>%

filter(

office=="COUNCIL AT LARGE",

candidate=="Kendra Brooks"

) %>%

mutate(ward=substr(warddiv,1,2)) %>%

group_by(ward) %>%

summarise(

pvote=sum(votes, na.rm=TRUE) / sum(votes/pvote, na.rm=TRUE),

total_votes=sum(votes/pvote, na.rm=TRUE)

) %>%

left_join(ward_turnout_19) %>%

left_join(ward_turnout_comp, by="ward", suffix=c(".19", ".comp")) %>%

mutate(turnout_ratio = turnout.19/turnout.comp),

aes(y=turnout_ratio, x=100*pvote)

) +

geom_text(aes(label=ward, size=total_votes)) +

scale_size_area("Total Council At Large Votes in 2019", label=scales::comma) +

expand_limits(x=0) +

theme_sixtysix() +

labs(

title="Kendra Brooks' base surged in turnout",

x="% of Vote for Brooks",

y=sprintf("Votes cast for Council At Large, 2019 / %s", comp_year)

)

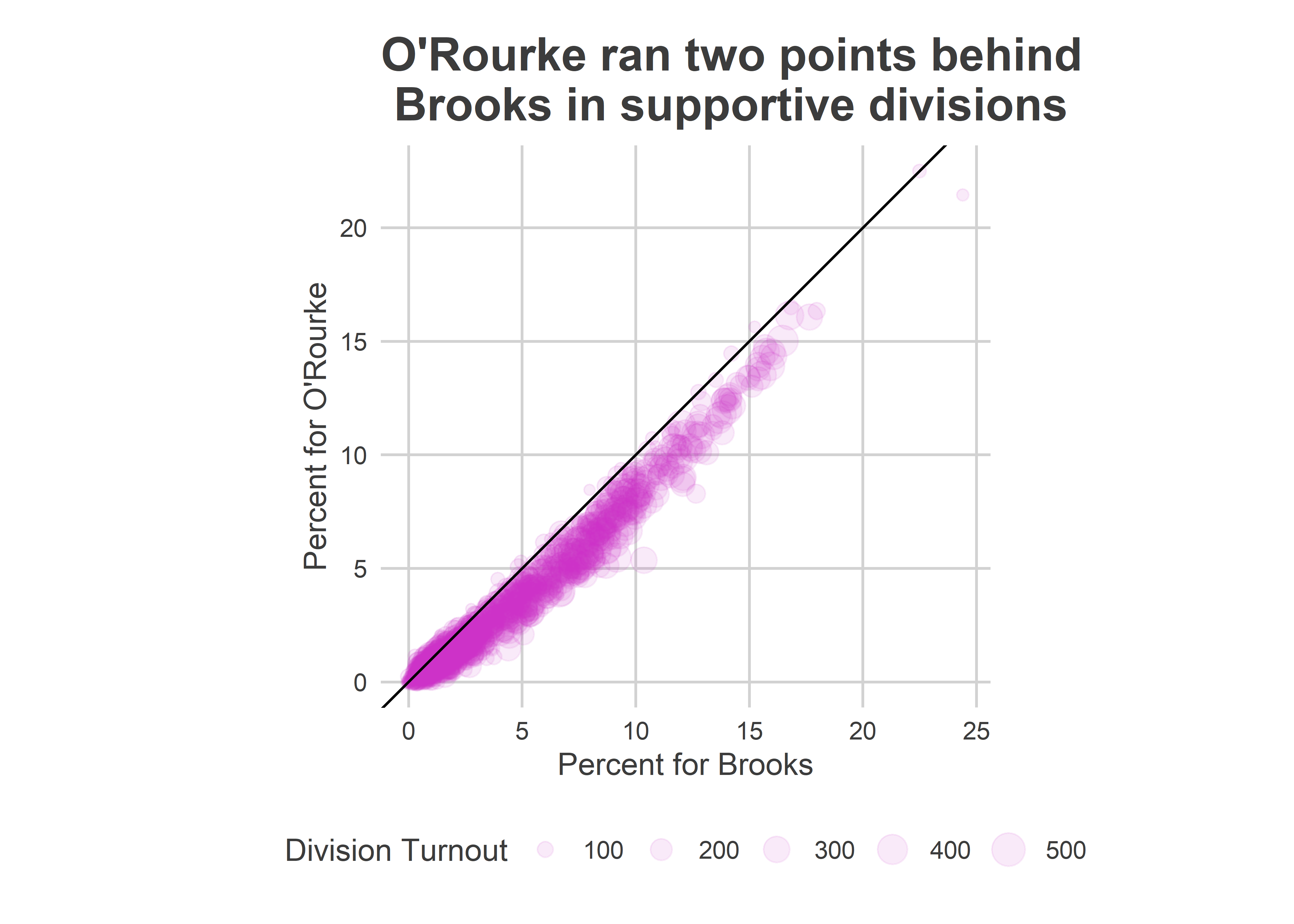

But that would seem to help O’Rourke too. Why did Brooks win and O’Rourke lose? He ran a steady 2 points behind her across their supportive divisions.

View code

turnout_df <- df_past %>%

filter(is_primary_office) %>%

group_by(year, warddiv, election) %>%

summarise(turnout=sum(votes)) %>%

bind_rows(

df %>%

filter(office=='MAYOR') %>%

group_by(warddiv) %>%

summarise(turnout=sum(votes)) %>%

mutate(year = '2019', election="general")

)

ggplot(

at_large_df %>%

filter(candidate %in% c("Kendra Brooks", "Nicolas O'Rourke")) %>%

select(warddiv, candidate, pvote) %>%

spread(key=candidate, value=pvote) %>%

left_join(turnout_df %>% filter(year == 2019, election == "general")),

aes(x=100*`Kendra Brooks`, y=100*`Nicolas O'Rourke`)

) +

geom_point(

aes(size = turnout),

color=strong_purple,

alpha=0.1

# pch=16

) +

scale_size_area("Division Turnout") +

geom_abline(slope=1) +

coord_fixed() +

theme_sixtysix() +

labs(

title="O'Rourke ran two points behind\n Brooks in supportive divisions",

x="Percent for Brooks",

y="Percent for O'Rourke"

)

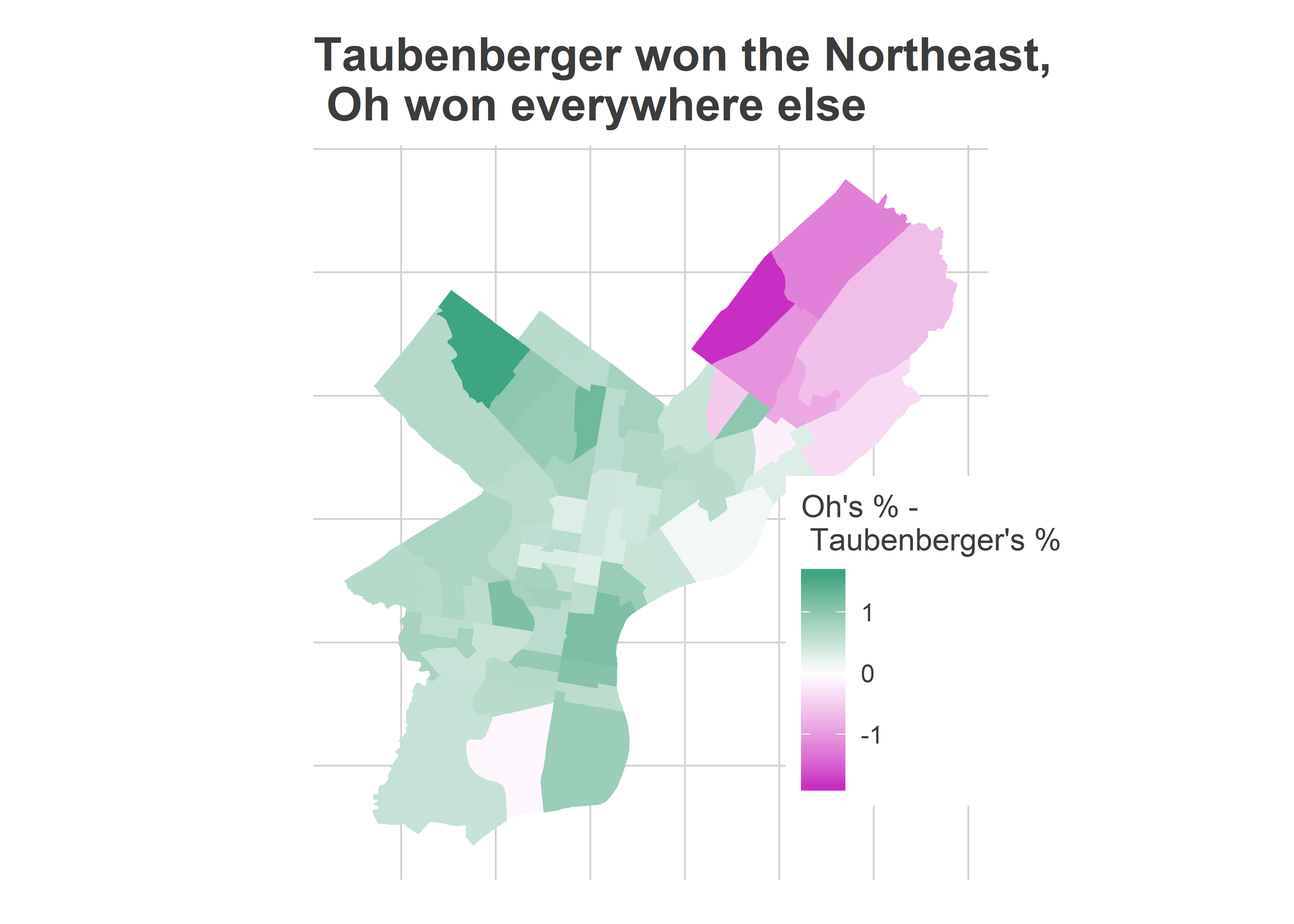

How about on the Republican side? Why did Oh win and Taubenberger lose? Taubenberger nudged out Oh in the Republican bases, but Oh outpaced him in the rest of the city. And the rest of the city has more votes.

View code

winsorize <- function(x, t=0.99){

cutoff <- quantile(abs(x), probs=t, na.rm=TRUE)

return(sign(x) * pmin(abs(x), cutoff))

}

ggplot(

wards %>% left_join(

at_large_df %>%

filter(candidate %in% c("David Oh", "Al Taubenberger")) %>%

mutate(ward = substr(warddiv,1,2)) %>%

group_by(ward, candidate) %>%

summarise(votes=sum(votes)) %>%

left_join(ward_turnout_19) %>%

mutate(pvote=votes/turnout) %>%

select(ward, candidate, pvote) %>%

spread(key=candidate, value=pvote)

)

) +

geom_sf(

aes(fill=100*winsorize(`David Oh`-`Al Taubenberger`)),

color=NA

) +

scale_fill_gradient2(

"Oh's % -\n Taubenberger's %",

low=strong_purple,

high=strong_green

) +

theme_map_sixtysix() +

labs(

title="Taubenberger won the Northeast,\n Oh won everywhere else"

)

Philadelphia’s Voting Blocs

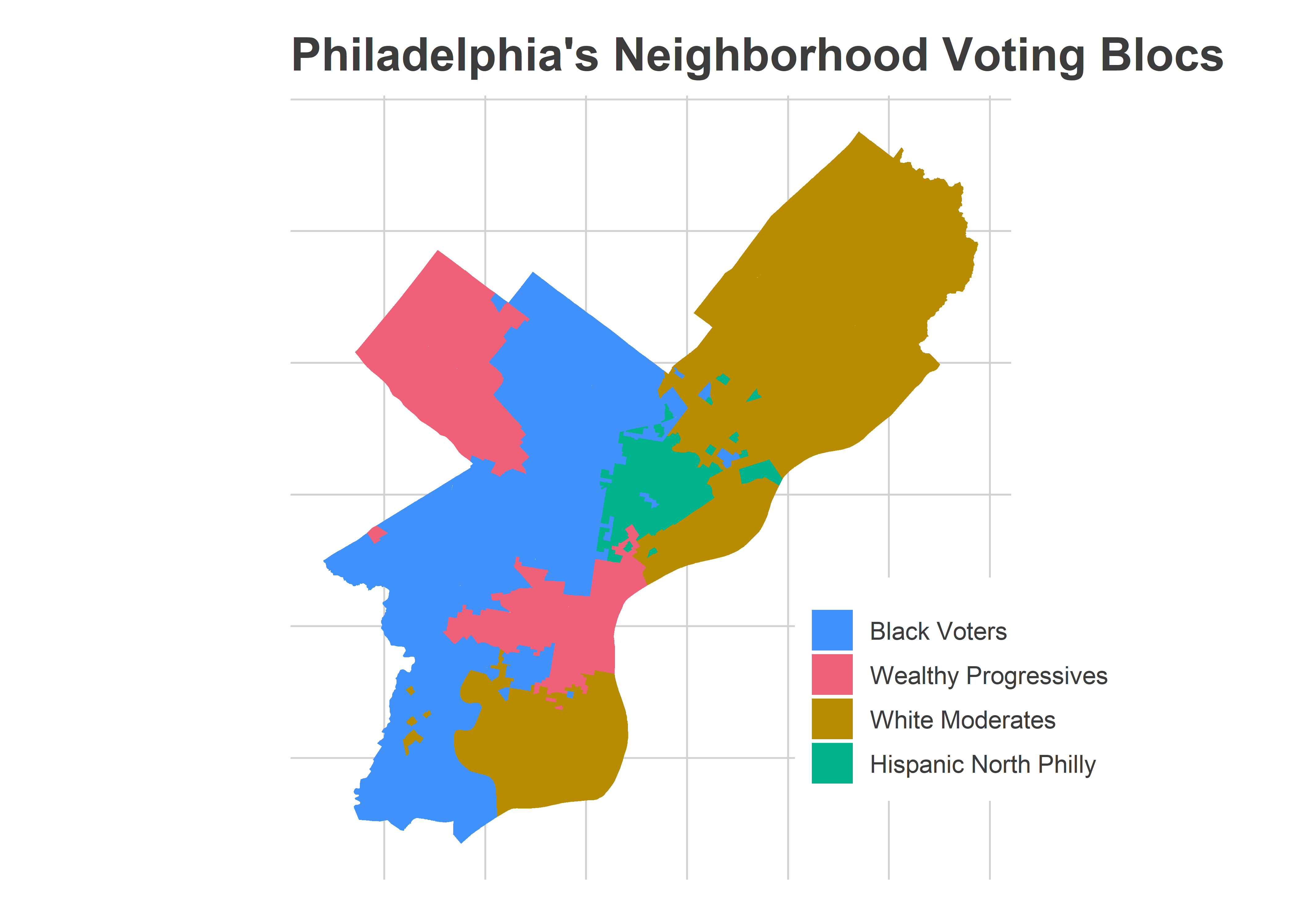

My new favorite way to cleanly describe a race is with Philadelphia’s Voting Blocs. I use historic correlations to identify sets of divisions that vote for the same candidates. The patterns are striking, and tell a clear story: Philadelphia’s voting is a story of race and class.

I’ve updated my data and tweaked the methodology since the first post, so here’s a new map of the voting blocs.

View code

cat_colors <- c(light_blue, light_red, light_orange, light_green)

names(cat_colors) <- levels(div_cats$cat)

ggplot(

divs %>%

left_join(div_cats)

) +

geom_sf(aes(fill=cat), color=NA) +

scale_fill_manual(NULL, values=cat_colors) +

theme_map_sixtysix() +

ggtitle("Philadelphia's Neighborhood Voting Blocs")

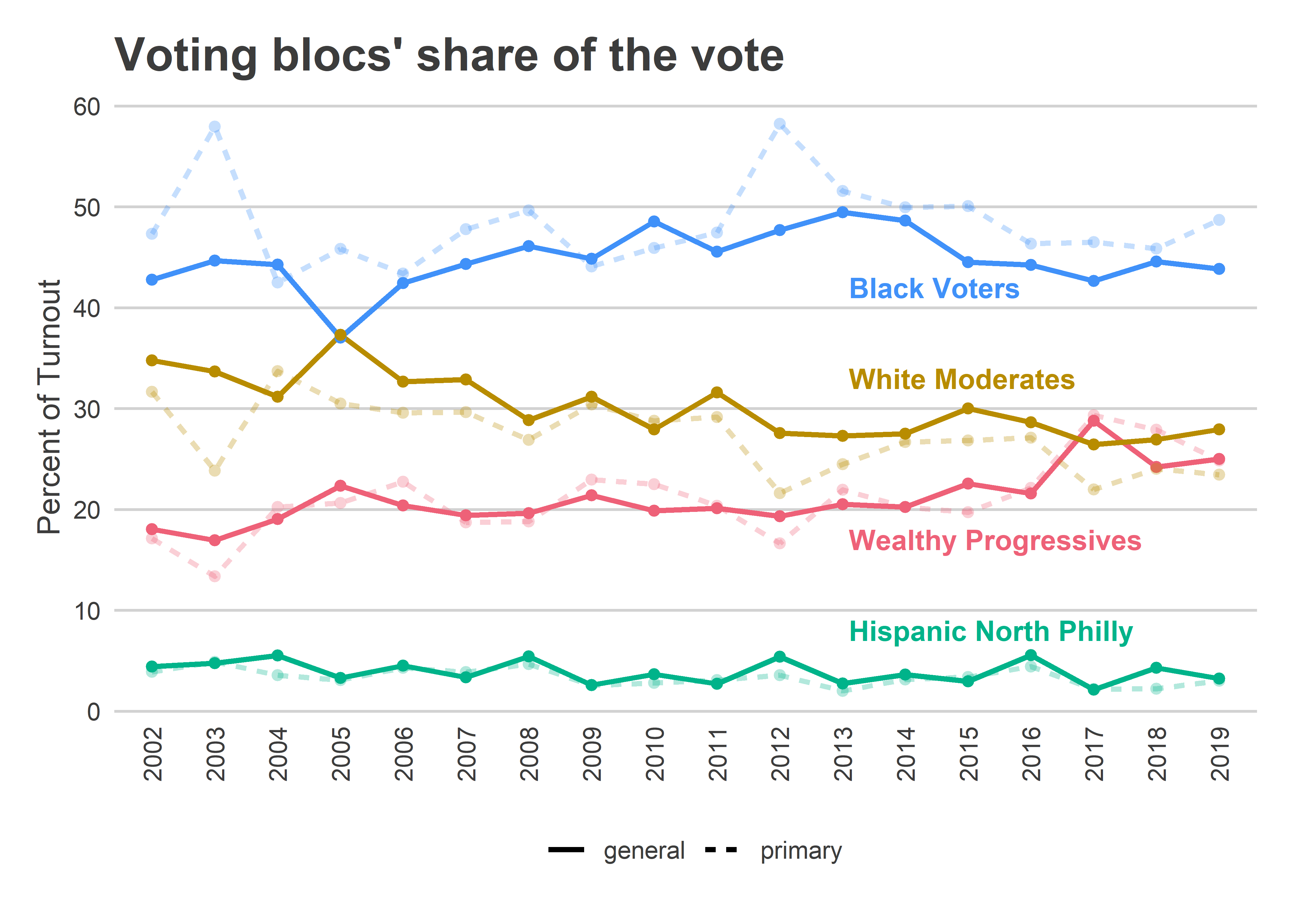

The Trump era has changed the city’s dynamics. After hovering below 23% of General Elections’ turnout up to November 2016, Wealthy Progressives had 29% of the turnout for Krasner’s 2017 General, 24% in 2018 and 25% on Tuesday.

View code

turnout_divcat <- turnout_df %>%

left_join(div_cats) %>%

group_by(cat, year, election) %>%

summarise(turnout=sum(turnout)) %>%

group_by(year, election) %>%

mutate(pct_of_turnout=turnout/sum(turnout))

ggplot(

turnout_divcat,

aes(x=year, y=100*pct_of_turnout, color=cat, alpha=election)

) +

geom_line(

aes(

group=interaction(election, cat),

linetype=election

),

size=1

) +

geom_point(pch=16, size=2) +

scale_color_manual(NULL, values=cat_colors, guide=FALSE) +

scale_alpha_manual(NULL, values=c(general=1, primary=0.3), guide=FALSE) +

annotate(

geom="text",

x=12.1,

y=c(42, 17, 33, 8),

hjust=0,

label=names(cat_colors),

color=cat_colors,

fontface="bold"

) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks=seq(0,100,10))+

labs(

x=NULL,

y="Percent of Turnout",

title="Voting blocs' share of the vote",

linetype=NULL

) +

theme_sixtysix() %+replace%

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle=90), panel.grid.major.x = element_blank())

Brooks would have won even if the turnout shares had looked like pre-2016, though. She received 8.6% of the vote in the Wealthy Progressive Divisions, and 3.2% in the rest of the city. The difference between Wealthy Progressives comprising 25% of the vote versus 20% gave her an extra 0.3 percentage points. That difference was the difference between a nail-biter and the romp that we saw, but didn’t itself cause the win.

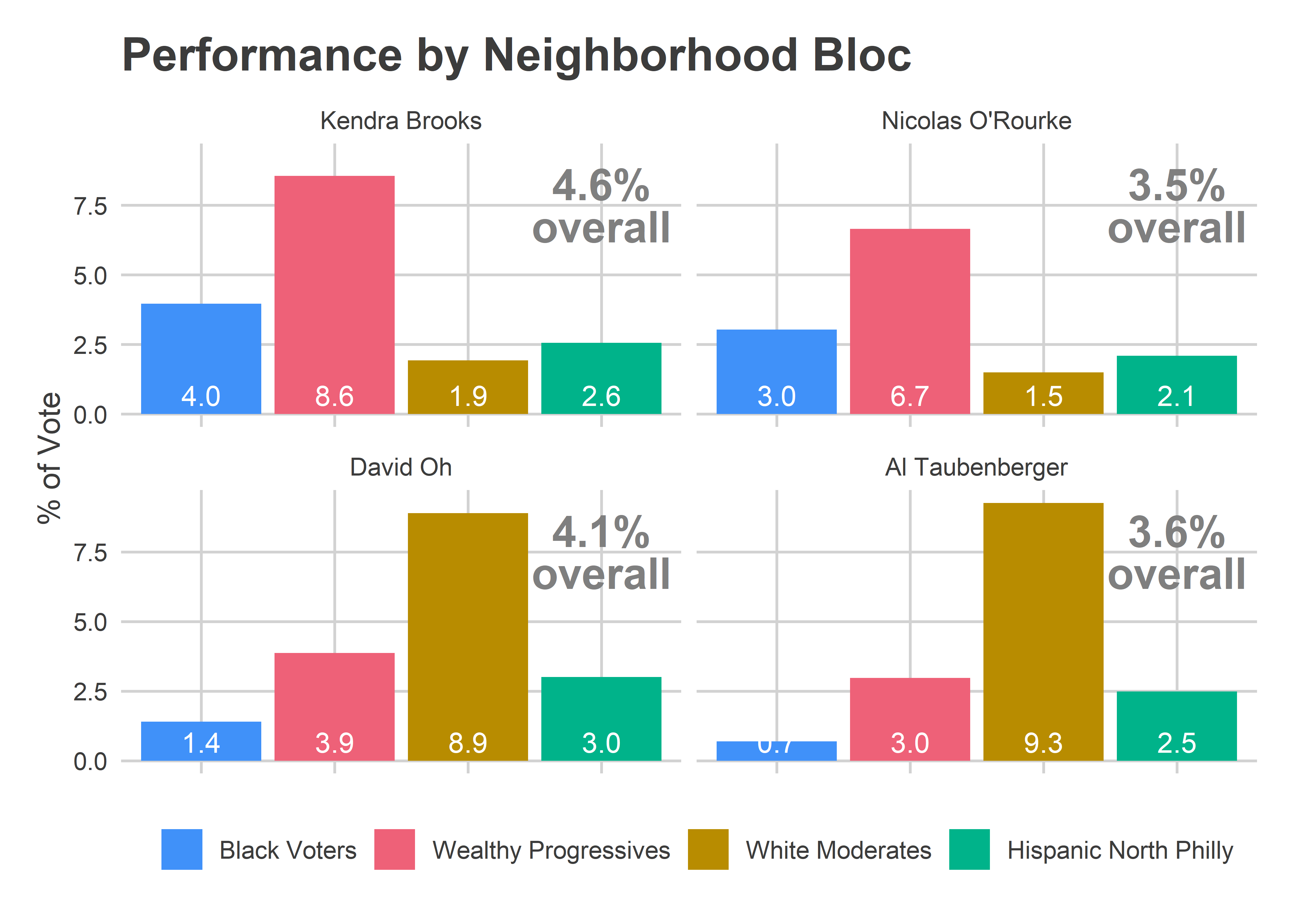

Instead, for both Oh and Brooks, it was the performance outside of their bases that carried them to victory. Performance by bloc makes it clear why Brooks and Oh won, and their party-mates came up just short.

View code

bar_df <- at_large_df %>%

left_join(total_votes) %>%

left_join(div_cats) %>%

group_by(candidate, cat) %>%

summarise(

total_votes = sum(total_votes),

votes = sum(votes)

) %>%

mutate(pvote = votes/total_votes)

overall <- bar_df %>% group_by(candidate) %>%

summarise(pvote = weighted.mean(pvote, w=total_votes))

ggplot(

bar_df,

aes(x=cat, y=100*pvote)

) +

geom_bar(aes(fill=cat), stat = "identity") +

geom_text(aes(label=sprintf("%0.1f", 100*pvote)), color="white", y=0, vjust=-0.4) +

geom_text(

data = overall,

aes(label=sprintf("%0.1f%%\noverall", 100*pvote)),

hjust=0.5,

lineheight=0.8,

x=4, y=7.5,

size=6, fontface="bold", color="grey50"

) +

scale_fill_manual(NULL, values=cat_colors) +

facet_wrap(~candidate) +

theme_sixtysix() %+replace%

theme(axis.text.x = element_blank()) +

labs(

x=NULL,

y="% of Vote",

title="Performance by Neighborhood Bloc"

)

Brooks won because she ran ahead of O’Rourke everywhere, including by a whopping two points in the supportive Wealthy Progressive divisions, and by one point in the voting-dominant Black wards.

Oh won because of his support outside of his base: he tortoised his way slowly but surely through the rest of the city, collecting votes in the Wealthy Progressive divisions (0.9 percentage points more than Taubenberger), Black Voter divisions (0.7 more), and Hispanic North Philly (0.5 more). My hunch is that’s a function of his greater name recognition and activity.

Why was I wrong?

When I looked at this race in August, I thought third parties were a long shot.

(In my defense, Helen Gym endorsed Brooks literally the day after I hit publish. I would have written the piece very differently had she pulled that unprecedented move 24 hours earlier.)

I wrote that Brooks would need 10.6% of the vote from Wealthy Progressives, and even then it would be toss up. Instead, she got 8.6% and cruised to victory.

What happened? The Black Voter divisions voted for her, and did so hard. Those neighborhoods hadn’t voted for non-Democrats before, and I proposed maybe she could get 1.7% in my high projection. Those wards are strongly organized by the Democratic Party, and hadn’t strayed from their Party loyalty before. But they voted for Brooks at 4%, more than double what I thought plausible. That’s the story of this election, and the reason the impossible happened.

How did the Working Families Party pull that off? I’ll let the real reporters work that out, but probably through some combination of running candidates that Black voters found compelling and a massive outreach program teaching voters about the intricacies of Philadelphia’s Charter and encouraging strategic voters.

So I’m gonna claim I wasn’t that wrong. 🙂