A number of Philadelphians find themselves engaged in politics like never before. Many are considering running for office. While you may not be eyeing a run for Governor, the 2018 primary includes the race for 3,372 Democratic Committeepeople. What would it take for you to be one of them?

What’s a committeeperson?

Philadelphia is divided into 66 political wards, which serve as the geographic unit for political party organization. The Wards are subdivided into 1,686 divisions. Divisions contain about 1,000 people, and typically cover about 11 city blocks. Your division dictates your polling place.

Both the Democrats and Republicans represent their divisions with two elected committeepeople. These elections are held every four years in the party primary. Every committeeperson is up for reelection in 2018.

The bulk of a committeeperson’s role is to be the foot soldiers for the party—managing get out the vote efforts and distributing endorsements. They participate in Ward meetings, and are the residents’ conduit for communications (the effectiveness of this depends on the Ward and committeeperson, obviously). In some Wards, committeepeople also participate in selecting candidates to endorse. Finally, committeepeople are the ones who select Ward leaders, in a vote shortly after their election.

For more reading, I recommend the Committee of Seventy’s Guide. But here, let’s look at the voting patterns, and what it takes to win. Being a committeeperson is a natural point of entry to city government. And, frankly, it’s the easiest race you could run.[1]

How many votes does it take to win?

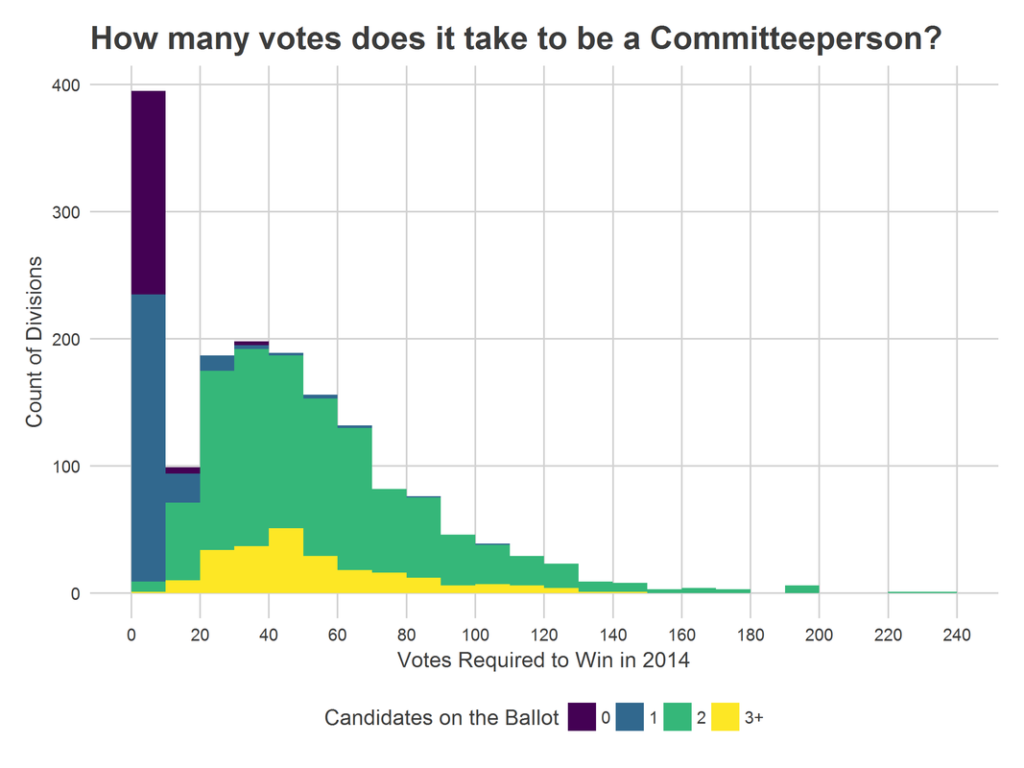

Many committee positions are left completely empty. In 2014, 348 of the 3,372 Democratic committee positions went unfilled. An additional 95 candidates won with only a single vote, and 214 winning candidates received ten or fewer. In the map above, win count is the number of votes received by the second winning candidate.

How do people win with so few votes? Many won as write-in candidates, without their name on the ballot. All 95 one-vote winners were write-ins, and presumably either wrote in their own name or have really proud mothers. In total, 275 candidates won as write-ins. Almost all of the write-in winners were in divisions with fewer than two names on the ballot, though amazingly 11 write-in candidates won in divisions by beating someone on the ballot.

Some 168 divisions (10%) had no candidates on the ballot, while 273 (16%) had one candidate. In the rest, 1,012 divisions (60%) had exactly two candidates, one for each position, and only 233 (14%) had a competitive race with three or more.

What to look for in May 2018

Petitions for committee candidates to get on the ballot are due March 6, 2018. If you’re interested, the Committee of Seventy provides a useful guide for

How to Run for Office.

Even if you’re not running for office, stay tuned. One of the important open questions of 2017 is the extent to which newfound national political energy will translate into local political engagement. Will our new political world effect city and state governance? May’s committeeperson race will be an important signal.

Footnotes

[1] I focus on Democratic committeepeople. If you want to be a Republican Committeeperson, the competition is non-existent.