I’ve downloaded the boundaries from pubintlaw, and created an interactive map. In order to project how each district would perform, I’ve aggregated the results of the races for President in 2016 and Governor in 2014. Let’s dig in.

The GOP’s proposal clearly creates compact boundaries that align with county boundaries much more often. While this is what most people focus on with gerrymandering, I think the compactness standard is nonsense: it is completely possible to waste a party’s votes with compact boundaries if perniciously drawn. In fact, the concentration of Democrats in cities means that even naive compact districts will almost certainly favor Republicans.

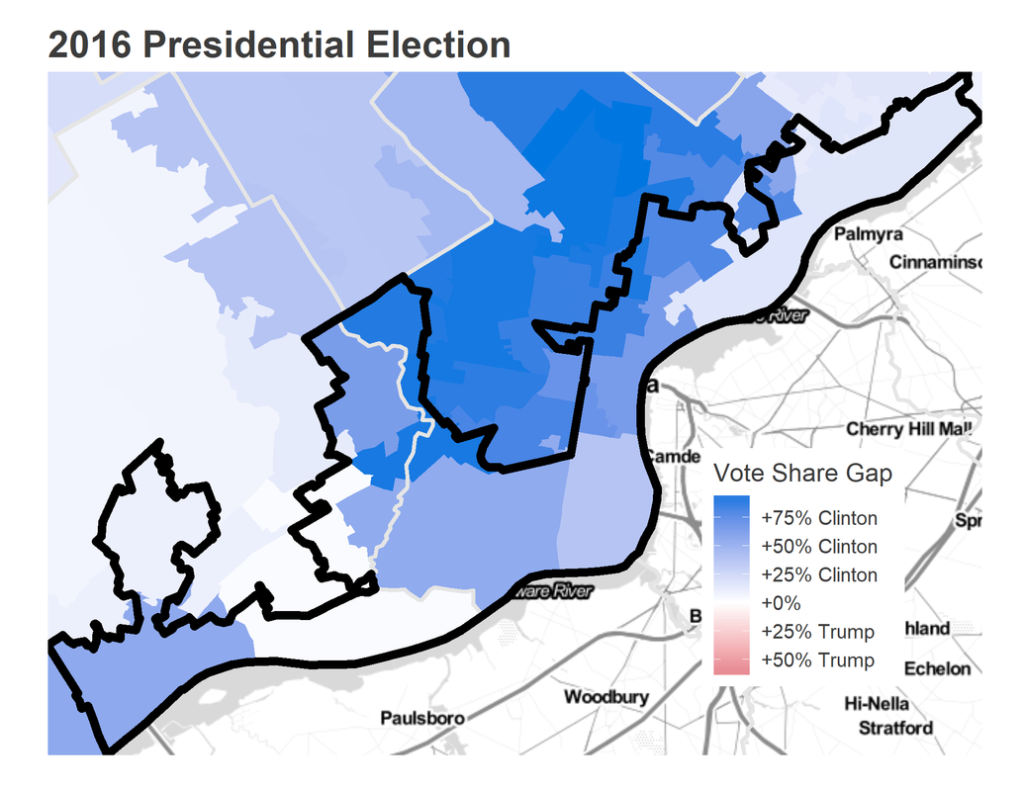

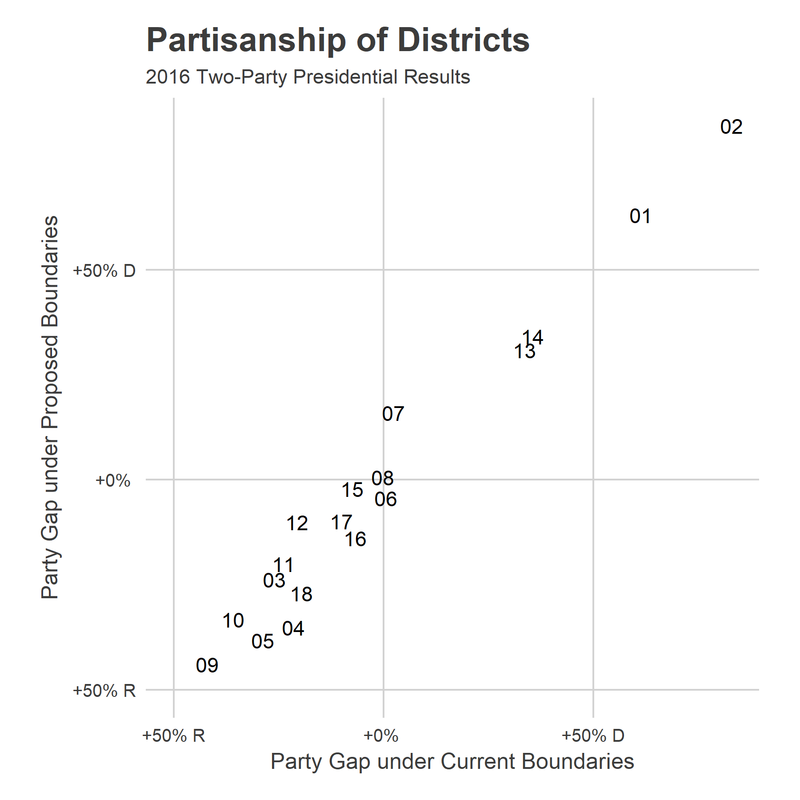

The new districts maintain the exact same Republican advantage as the prior ones. To assess this, let’s look at the outcome of the 2016 Presidential election. Donald Trump narrowly won Pennsylvania, with 48.2% of the vote to Hillary Clinton’s 47.5%. However, he won 12 of the Congressional Districts to Clinton’s 6 (and in total 13 Republican House members won to Democrats’ 5). This imbalance between topline vote and district count was achieved by packing Democrats all into a few districts, to waste their votes in landslide elections, leaving comfortable but not wasteful Repubican wins in the rest of the state.

With respect to the 2016 Presidential election, the new boundaries look a lot like the old ones:

District PA-07 swings hard to the Democrats. That district, famously gerrymandered as “Goofy kicking Donald,” is a convenient sacrifice for Republicans as Representative Pat Meehan has already stepped down from the race amidst sexual misconduct allegations.

By sacrificing PA-07, Republicans make PA-06 a more likely Republican seat. The district, covering the farther-West Philadelphia suburbs, had been narrowly won by Clinton, but would now be a 4.4% Trump win.

PA-08 remains the most evenly split district. It covers the suburbs to Philadelphia’s Northeast: Doylestown, Newtown, et al. It was and would remain essentially 50-50. Clinton would have won it by the slimmest of margins in 2016.

A strong Democratic 2018 could still swing seats. Districts 12 and 17 would have been Trump wins by 10 percentage points under these boundaries. These are the types of seats that we would expect to see competitive in a Democratic wave election. In fact, the logic of gerrymandering may mean that wave elections have more power: gerrymandered seats should be safe but not too safe, to avoid wasting votes, which may put a lot of them in play in a 10-20% Democratic swing.

But we shouldn’t lose sight of just how troubling the baseline assumption in that logic is: Democrats basically need a wave election just to break even. In the dead-even state-wide election of 2016, Republicans won 13 seats to Democrats’ 5 (Trump won only 12; another district split). Just because Democrats may be able to overcome the disadvantage to barely break even doesn’t mean that the districts are fair.

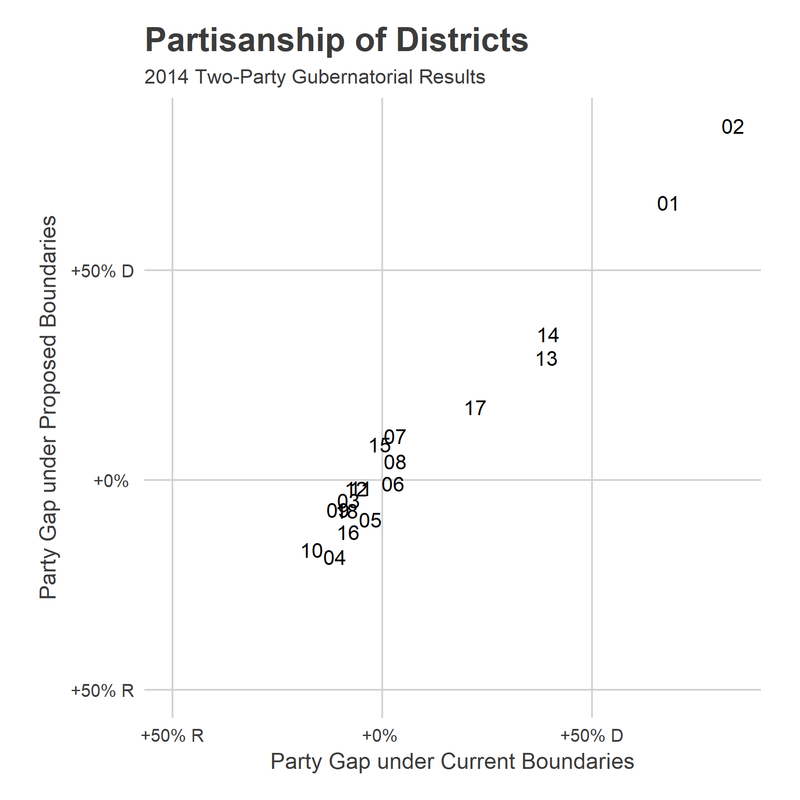

Just to check that 2016 wasn’t a fluke, here is the same plot for the 2014 Governor’s race.

The wasted votes are particularly breathtaking here: Corbett wins 10 of the 18 seats in both scenarios despite losing by 10% overall. And his largest win in a single district is by 18% in the new PA-04; Democrats would win by that much in *four* districts. Their votes are being concentrated, and wasted.

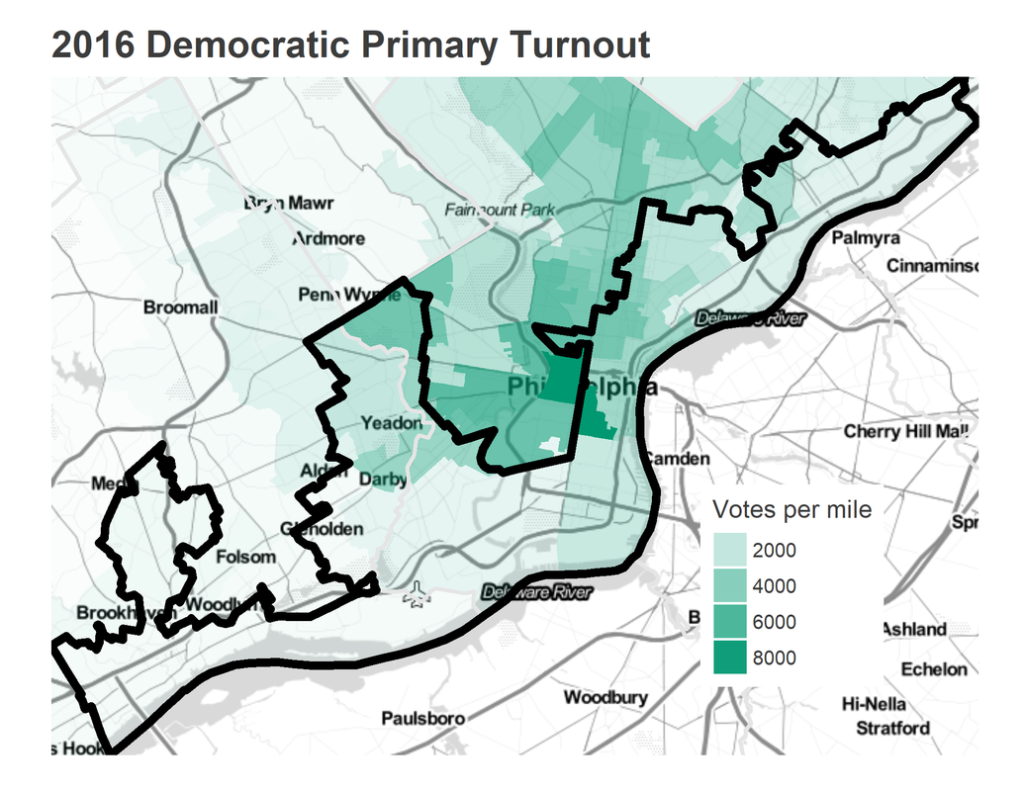

To predict results within the new boundaries, I need to rely on data calculated from previous boundaries.

I am using election data from the amazing folks at openelections.org. I begin with election results at the smallest available unit of geography, the State House Districts. When a district is entirely contained within one of the new Congressional Districts, I simply add the votes. When the state house district is split between two or more of the congressional districts, I allocate its votes based on the 2010 census population-over-age-18 of the overlapping areas. Often, analyses apportion these voters based on area, but I expect using population-weighted measures to be much more accurate. Code available upon request (or once I organize my github repository).